165 years, 3 months and 20 days

ago 200 Indian warriors attacked a settlement of 20 men and 40 women and

children at a place in northwestern

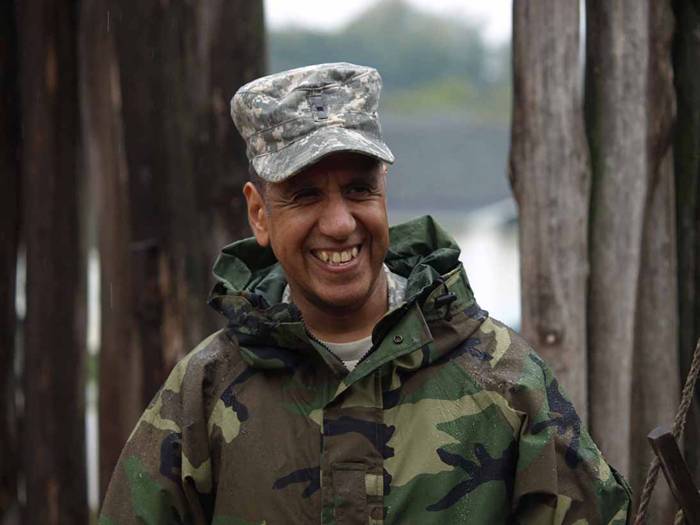

Today, 20 modern warriors of the

My wife is one of those

soldiers and I was invited to accompany her group. So at six o’clock on a Sunday morning, we

assembled. Major Harbaugh briefed us on

the Black Hawk War and particularly the Battle of Apple River Fort.

Our involvements in

We then left for the Apple

River Fort.

We would travel border-to-border

across the northernmost part of

Happily, the rain was very

light at the battle site and would cease during our visit.

We regrouped at the museum

nearby the battle site and were engaged by the knowledgeable staff there.

The war lasted from

mid-May through July of 1832 with the

This raid was led by Black

Hawk, the Chief for whom the war is named.

He had seen battle as (what we would call) a squad leader at the age of

15. He was 65 at the time of this raid,

and so had a half-century of experience.

After the war he dictated

a 79 page autobiography. He describes

this raid on pages 62, 63 & 64. I

note two points. According to him:

(1) Several days before his raiding party left

for the battle site he said (emphasis mine) to his warriors: “Now is the time to show your courage and

bravery and avenge…”

and (2) On the morning of the day they would attack

he told his warriors that there was a “great feast” to be had at the battle

site.

So it seems that Black

Hawk had intended to kill everyone and then take the stores. Because the entire settlement found shelter

behind a stockade fence, Black Hawk simply took the stores and left.

Still, with a ten-to-one

supremacy of numbers, the settlers had to dissuade him from overrunning their

small fortification. The 45 minute

engagement resulted in one settler killed.

The 20 militia were able to hold-off the 200 warriors because they had a

force-multiplier in the 40 women and children who were in the fort with them.

A flintlock musket can be

fired a maximum of three times per minute because there are twelve steps in its

manual of arms. Because the women and

children would reload, the men could aim and fire four or five times per

minute.

These two interpreters,

dressed in period costume, were also very knowledgeable.

So we inspected the fort

as it had been reconstructed.

And then we left. Robin and I continued westward to

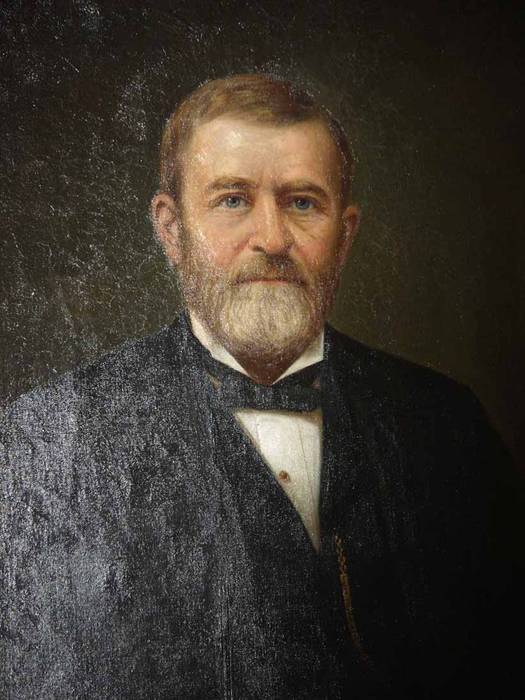

And then we found Grant’s

home.

He received this house as

a gift and never lived in it permanently.

He did however visit it regularly and so it was

We then found downtown

Robin found a storefront

with a cat.

And she found a store

promoting Brest Cancer Awareness Month with pink balloons on their door. Consider this photo our contribution to that

effort.

Update, one week later:

I was in

“Whilst lying here we have

thrown up a strong stockade work flanked by four block houses, for the security

of our supplies and the accommodation of the sick. I shall garrison it with a few regulars

(sick) and 150 to 200 volunteer troops under an Army Officer.”

The entire war lasted only

three months. That dispatch was sent two

weeks before the decisive Battle of Bad Axe and two months before the fort

would be abandoned. Early settlers would

cannibalize the materials and the fort would disappear entirely in five

years. Nine years after the war, those

early settlers named their settlement named “

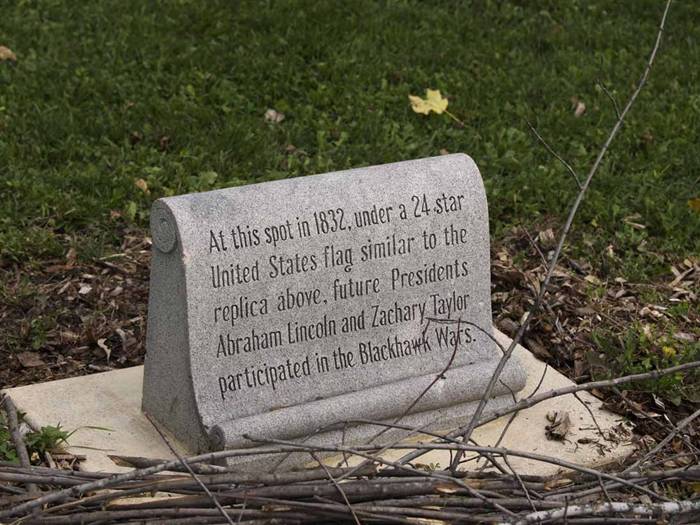

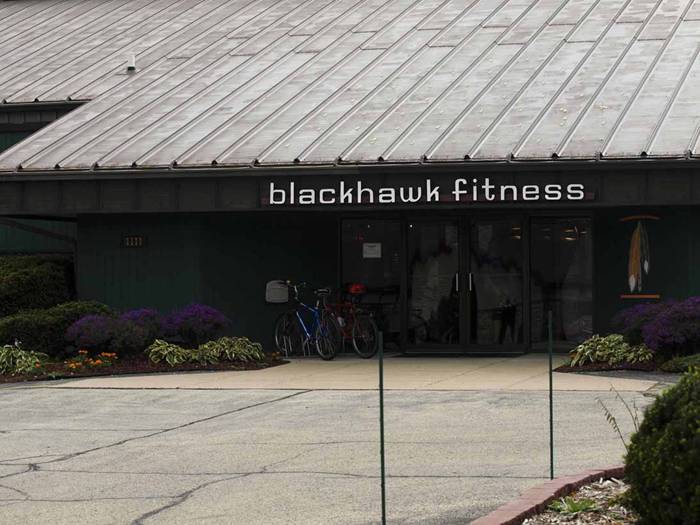

I found both the marker

above and the gym below in this small town.

It seems to me that making the word compound is similar to speaking of

the Georgebush Presidency.

About 1967, the town built

a replica of

The original site has been

otherwise developed, so the replica is just west of town, a part of the

I am happy to report that

I found one worthy tribute to the great Chief.

The Black Hawk Tavern displays a fierce likeness of him and offers a

one-pound burger named for him.

Jefferson, Wisconsin is

located six miles north of Fort Atkinson and the proximity breeds a rivalry. The tavern window announces that